Manbok Kim remembers the house she fled 66 years ago as if it were yesterday. “We had a large orchard,” she recalled. “There were so many apples on the trees.”

Now 87, Kim is one of 500 North Korean refugees who have contributed a drawing of the home they were forced to flee during the Korean War, as part of a public artwork by the South Korean artist Ik-Joong Kang.

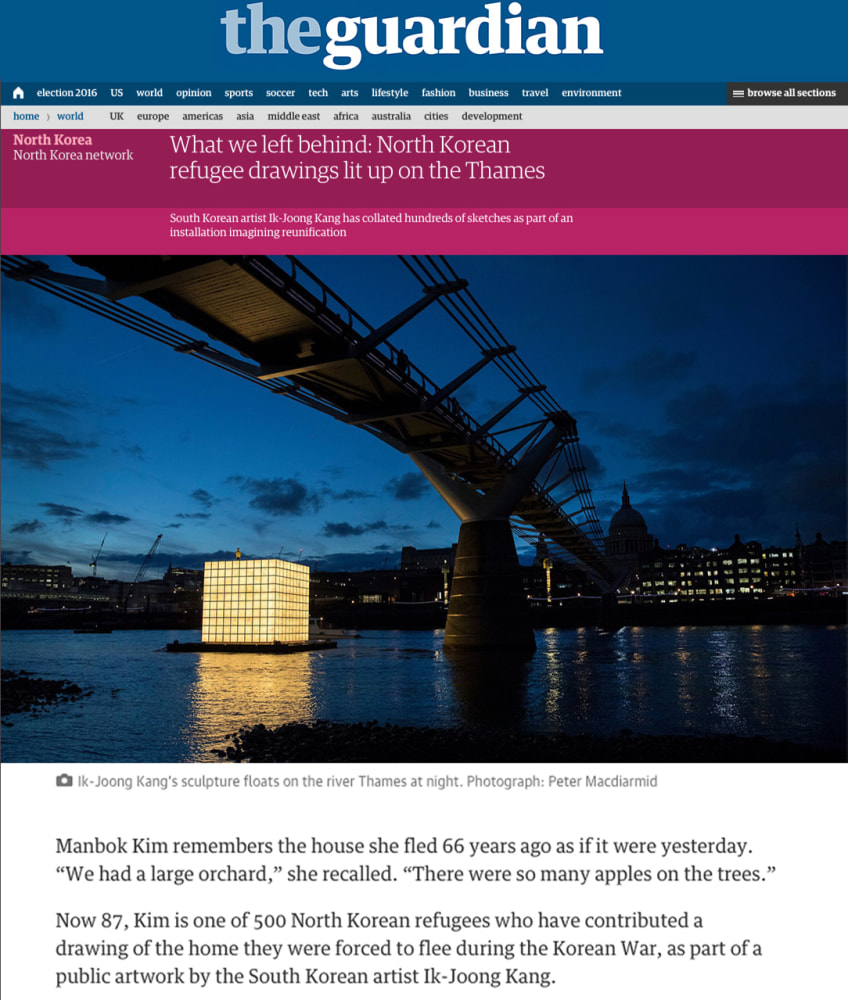

The floating installation, part of the Totally Thames festival that opens on Thursday, is a seven-metre-high illuminated cube constructed from hundreds of 70 x 70cm drawings, which were transferred from palm-sized sketches on Korean rice paper.

All the participants fled the North during the Korean war, which ended in 1953 in an armistice, not a peace agreement. The two countries have technically remained at war ever since, and many of the North Koreans who fled have been permanently separated from their loved ones since, forced to build a new life after the border was effectively sealed.

In the decades since, North Korea has become increasingly secretive and isolated. In a report released last year, the UN accused the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, of crimes against humanity. The report concluded that the country’s leadership was committing systematic and appalling rights abuses against its own citizens on a scale unparalleled in the modern world.

To find participants for the project, Kang visited South Korea’s numerous naengmyeon restaurants, which serve a popular northern speciality of buckwheat noodles with ice.

With a team of volunteers, the artist collected stories and drawings from the refugees he met. “It was an amazing emotional experience,” Kang said. “At first, they were very shy. They told me: ‘No I cannot, I cannot even draw.’ Then they paused and thought about their hometowns, and their families and friends ... and they were overwhelmed with emotion.”

Among the 300 volunteers gathering drawings was the South Korean unification minister, Hong Yong-pyo, who was also deeply moved by the process. “When I saw him [Hong] crying, I thought, ‘He really cares’. Maybe he will make it happen ... There is hope for unification,” Kang said.

There are an estimated 200,000 North Korean refugees living in South Korea. Many of them have spent most of their lives in the South and have never been able to revisit their hometowns, an important part of Korean culture.

“Paying a visit to an ancestor’s grave is [a] very important ritual, especially on the day of Chuseok [the Korean version of thanksgiving], or other festive days,” Kang said. “This year’s Chuseok is 15 September and tens of millions of Koreans will be jammed on the highways to go back to their hometowns. It’s a real mass migration. Chuseok is one of the happiest days to some people and the saddest day to others from the North.”

Art for reunification

Kang was born in 1960 in South Korea. “During the 1970s, signs and slogans of ‘bangong’ [anti-communism] were everywhere: on every street, government buildings and schools,” he said. “We were taught [that] communism was evil.”

In 1984, the artist moved to New York. On his daily commute into the city, he painted on three-inch canvases that he carried in his pocket. By the time he was invited to represent South Korea at the 47th Venice Biennale in 1997, he had created more than 200,000 works.